When I heard that Rod Stewart was coming to town I got the name of his management company off the back of an album cover and contacted the London office to request an interview. I phoned quite a few times over the course of a month. On each occasion—the same thing—I was asked to give my name, rank, and serial number, then politely placed on, you know, eternal hold—until I could no longer feel the receiver in my hand. I never got further than the receptionists. My phone bill that month was a gasping $200+—which, at that time, in my early 20s, would probably be equivalent to over $1 million in 2014 U.S. currency—more or less.

One day the GM of WNOK-FM called me and said, “Rod Stewart wants to see you,” sounding as surprised as I was.

“Me?”

“Yeah. The morning after his concert. He’s staying at the Hilton Townhouse on Gervais. You’re to go to the front desk and ask for a Mr. Toon.”

I couldn’t have been any more elated. As the date drew near, however, I started getting butterflies. I was new to the radio business and had only interviewed a few Southern rock bands at an outdoor concert on a farm in Rockingham, NC . Rod was a big time international rock star.

To say I was a bit on edge the day I ventured the Hilton Townhouse (Clarion Hotel today) to meet Rod is an understatement. I actually stalled outside his room door—where the gravity of the occasion collapsed on my shoulders and worked its way through my nervous system down to my wavering knees. But the human mind is like lightening—in the span of a single micro second, two micros tops, I concocted a perfectly reasonable excuse to explain why I didn’t get the Rod interview—and I came very close to cutting and running. I just didn’t feel like I had the confidence to effectively communicate with Rod on a one-to-one same level relationship—or even a deeply gawking goofy level for that matter.

I finally, reluctantly, forced myself to knock on the intimidating door. No turning back now, I thought. I tried a little psychology on myself. There’s likely no one here. I mean, why would Rod Stewart hang around for me? A conservative-looking, well-dressed man answered and introduced himself as “Tony Toon,” Rod’s personal manager. “Rod’s in the shower, come on in. What’s your name?” he asked.

While I searched for an outlet to set up my recorder, Mr. Toon moved across the room, and stood by the window, looking out over the city, off into the distance, as if he was an invading general surveying territory that his army had just conquered. “Did you go to the show last night, Wayne?” Mr. Toon asked, maintaining his attention out the window.

“I couldn’t. I had a school thing.”

Mr. Toon’s upper body swiveled my direction, and in a rather cryptic voice warned, “Whatever you do, don’t tell Rod.” And he returned his attention back to the window. I made a note of that.

Like an entourage, warm clouds of shower vapor followed Rod when he emerged from the bathroom, holding a towel, barefoot and shirtless, wearing only a pair of cream slacks—his hair was mostly wet, yet several of the famous spikes managed to point upward. Mr. Toon introduced us, left the room business-like, and Rod and I sat alone, facing each other on opposite queen beds.

“Hey, the BBC uses that Uher model,” Rod said, pleasantly surprised to be familiar with my recorder, while I felt a very grateful surge of cred.

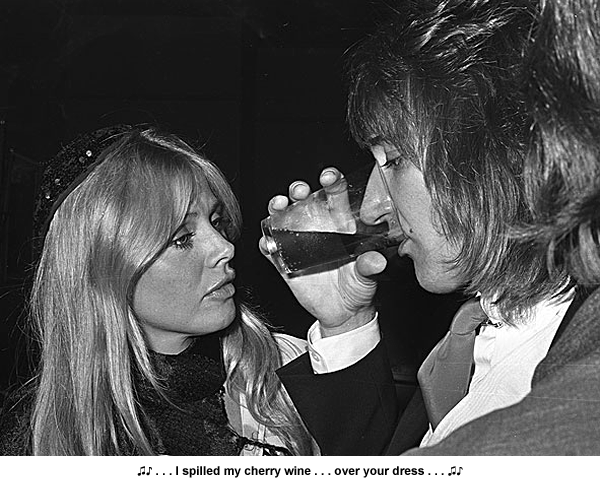

There was a lot going on in Rod’s life at the time. He had a new album out, “Atlantic Crossing,” which was doing well. He was leaving Faces, the band he had been with for quite awhile, to go solo. Having just moved from England to Los Angeles, Rod was applying for US citizenship. And he had, only a few months earlier, met and become smitten with Swedish actress, Britt Ekland—the lady love who contributed “naughty whisperings” to the track and inspired him to write “Tonight’s the Night”—his biggest hit ever—holding #1 on the charts for seven weeks—the longest ride at the top of the charts since The Beatles’ “Hey Jude” in 1968—the colossal hit single from the album that would immediately follow “Atlantic Crossing.”

But now Rod was here, on the road, with me, and Britt was in LA. It wasn’t long before it was obvious that he was suffering a double whammy of homesickness and lovesickness.

I dove right in best I could. “Tell me about your new album. How’s it doing?”

“Not to blow me own horn or anything but right now it’s the number one album in England. And the single, “Sailing”, from the album, is number one in Britain. I love ’em in Britain. And miss ’em as well.”

“The title, “Atlantic Crossing” came from the fact that I moved away from England to come here, to America, because of the tax situation. They want everything you earn over there. It’s like highway robbery. They take 98% of everything you earn! You have a dollar—they take 98 cents. I don’t think that’s very fair, do you?”

“But that’s because your earnings have reached a higher tax bracket, right?”

“Well . . . it’s not my fault . . . I just sing . . . and that’s all I know.” (Little knowing laugh from Rod)

“How has life changed for you since becoming a rock star?”

“I don’t think I’ve changed that much. Not really. I just have a bit more money.”

“You mean a lot more money.”

“How do you know? You haven’t seen my bank account! (Rod laughs) No, I know what it’s like not to have any money. So if I never have money again, fuck it, you know? The money buys you freedom. No doubt about that. You can do things . . .

“Like what?”

“Well . . . when I finish this tour, I’m going on a safari to Africa. I wouldn’t have been able to do that back when I was digging graves for a living.” (A story that ran for decades until Rod came clean and admitted that he had not dug graves but rather measured the plots in the cemetery)

“Is the image that the public has of you different from who you are in private?”

“It’s a terrible word to use really, ‘image.’ What that image is I don’t know.” Rod said, looking at me for an answer.

“Uh, I think it varies with people,” I replied, slightly concerned I might have opened a bad can. “You know, like how you have a reputation for partying, trashing hotel rooms when you’re on the road. Throwing TVs out the window.”

“Well if you would see the kind of service we get sometimes you’d understand. You order your breakfast and it all comes up cold. You send it back and it all comes up cold again. It goes out the window then, I tell you.”

I quickly changed tack. “What about performing? How do you prepare before you go on stage? Are you nervous?”

“We employ a couple of cheerleaders backstage. What their job is . . . what they’re paid to do is to encourage us and say things like , ‘Come on lads, let’s get it on!’ But, yeah, I guess you’re always nervous for the first couple of numbers. Walking up the steps . . . to the stage . . ., it’s like . . . I suppose it’s like going up to the gallows, in a way. ‘Cause I don’t have any fixed speech of what I’m going to say. I just get up there and wiggle me arse for the first couple of numbers and hope for the best. I must admit I was swearing a bit last night. In the nicest possible way, of course.” Rod scanned my eyes—seeking feedback.

His eagerness to get some feedback from last night’s show caused me to wish I had gone to the concert. I deflected his comment, however. I was new to the business but one thing I was certain of, that was always true: Never, ever act against the advice and counsel of the rock star’s road manager. And when I considered the tone of Mr. Toon’s warning, “Whatever you do, don’t tell Rod that you didn’t see the show,” and his solemn posture standing at the window, I understood it was in everybody’s interest that I not confess to Rod that I had missed his show.

Fortunately, it had always been very natural for me to walk the thin line. I was gifted to deceive well without technically telling a lie. A combination of well-placed facial expressions and pointedly ambiguous language with the odd affirming sound—I was born to deceive wisely.

“What did you think of the way we stacked the kit on the stage last night?” Rod asked.

I nodded and raised an eyebrow.

Rod’s eyes looked right through me. “It takes quite a lot to accomplish something like that. I bet you haven’t seen many bands do that, have you? In fact, I bet you haven’t seen any bands do that.”

He knows, I thought. He knows I didn’t go to his show. I’m certain of it. I really had a strong urge to tell him. Apologize and get it over. I had a school thing and couldn’t make it. He would understand. But what if he didn’t know? What if I confessed and he stood up and exploded over me? What if Rod Stewart tossed me out the window like a plate of cold eggs? And then Mr. Toon’s grave warning rang my cortex like hells bells, “Whatever you do, Wayne . . . don’t . . . tell . . . Rod . . .” What could I do?

I’ll tell you what I could’ve done, ok? I could have excused myself, packed up and got out of there tout de suite is what I could’ve done. And if I would have known, what lay ahead for me, in just a couple of moments, I wouldn’t have bothered to even excuse myself—I would have just grabbed the Uher and bolted for the door, without saying ‘thank you’ or ‘kiss my arse’ or anything. And you know what? I would have been very glad for it too.

(continued at 1st Prize Prize Prick II)

Loving these stories, Wayne. Keep them coming.

One of the best concerts I ever saw was Rod & Faces at the Charlotte Memorial Stadium. John Mayall and Cactus were there. Great show.

I thought the end of the story was going to be posted today?

Where’s the rest of the story?

Sorry yall. I didn’t know anyone was paying attention. Rest of Rod Stewart story is up now.