The last time we spoke Earl casually referred to a health issue. I had no idea until later that it was a serious illness. We had talked over a period of a year about ghostwriting and publishing the story of his full and remarkable life. Averse to the idea at first—his personality naturally opposed to self-promotion—he didn’t think his memoir would be of any meaningful interest to others. When I could get him on the phone, he put me off on each occasion, but he finally warmed up to the project—accepting that it might be a good legacy for his family. “OK,” he said. “I’m about over this health thing. Give me a couple more months.” He had characterized his cancer like it was one of the legions of hapless batters he made quick work of during his storied baseball career.

I first heard his name shortly after my family had moved from Germany to South Carolina. Classmates at Congaree Elementary School were talking about this local kid who pitched in the Little League World Series. “Earl was so good, the batters on the other team were crying,” one of them said with the kind of awe normally used for speaking about legends like Mickey Mantle and Roger Maris.

I met Earl a couple years later at R.H. Fulmer Junior High School. On the breezeway between classes he came up behind me and a schoolmate and told us we were moving too slow. We scooted over and as he went ahead he turned around and snarled at my Beatle-wannabe hairstyle. After he had safely passed and was out of range, I asked my friend, “Who does that asshole think he is?”

“You don’t know who that is? That’s Earl Bass!”

At the time I thought Earl was arrogant, but looking back, it’s surprising how modest he was. On the field, confident always. Off the field, generally humble. At Airport High, he starred and would become the leader in each of the Big Three varsity sports. He carried our school on his back season after season. Getting his teeth knocked out on Friday nights and recovering over the weekends. When our team sucked, we could always reply to trash-talking rivals by referring to the pride of our school’s sports excellence: “Earl the Pearl,” as many liked to call him. But I never used that nickname—because it reduced him to a mere costume gemstone and he was greater than that. I called him “Superman”—but not to his face—he would have hated it.

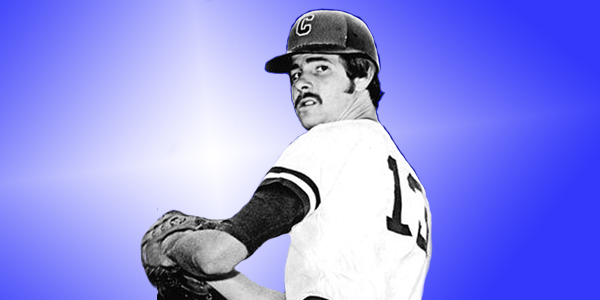

At the University of South Carolina, while most of us struggled to make it to our morning classes, Earl became a principal force in lifting the Gamecocks baseball program up to an elite level on the national stage. An All-American, he set records at USC that remain to this day. After he graduated to professional ball, he became a man in full. Perhaps the pearl epithet applied well to Earl during his pro years; for like the making of a fine pearl, Earl acquired, through trials of circumstance and freedom, more sublime layers of character—that shaped him into someone with finer grit and luster—sharpened the charity inside him—and embedded in him a major-league concern for others.

God bless Earl Bass.